Tibet 101

Tibet 101 is about educating the international community about the real situation in Chinese-occupied Tibet.

It is also about sharing why Tibet matters.

As China’s censorship and propaganda increase, a whole new generation is raised with limited knowledge of Tibet. Worse still, they are exposed to China’s version of the Tibet story.

Through our lobbying and campaigning, we educate the public on the various issues facing Tibetans.

9 quick facts about Tibet

1)

Tibet is a country in the Himalayan mountains, strategically located between India on the south and west and China on the north and east.

2)

Prior to China’s invasion in 1950, Tibet was an independent country with its own government, military, national flag and currency.

3)

Tibet has a total land size of 2.5 million square kilometres. It is one-quarter of modern China. It is almost half of the European Union. In the Australian context, it is slightly smaller than Western Australia.

4)

Tibet is the least free territory in the world, tied with Syria (Freedom House report 2021).

5)

Buddhism has been the main religion in Tibet since its arrival from India in the 8th century. Bon is the native religion which continues to be practised by a small section of Tibetans. There are also a very small number of Tibetan Muslims and Christians.

6)

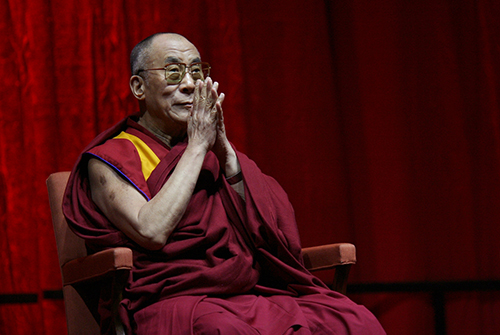

While Tibetan Buddhism has spread to all corners of the world, inside Tibet, Tibetans do not have the freedom of religion. Photos of the Dalai Lama are banned and monasteries are under the direct supervision of the communist Chinese government.

7)

Chinese policies are designed to wipe out Tibet’s unique cultural identity and assimilate Tibetans into Chinese culture. Mandarin is the dominant language in education, government and business.

8)

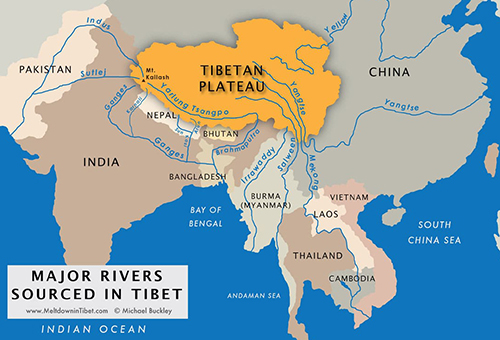

Tibet is called the Third Pole as it contains the largest reserve of freshwater outside the Arctic and the Antarctic. It is also the source of all the major rivers in Asia including the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Mekong and Yangtse.

9)

Tibetans continue to resist China’s occupation of their homeland. After escaping to India in 1959, the Dalai Lama established the Tibetan Government-in-Exile in Dharamsala. He is the spiritual leader of Tibet.

FAQs

1) Where is Tibet and how big is it?

Tibet lies in the heart of Asia with India to the south and west and China to the north and east. Smaller countries bordering Tibet are Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar (Burma). On its north western border lies Chinese-occupied East Turkestan (Chinese: Xinjiang).

Tibet has a land size of 2.5 million square kilometres, constituting one fourth of modern-day China.

2) How does Tibetans’ reference to Tibet differ from that of China’s?

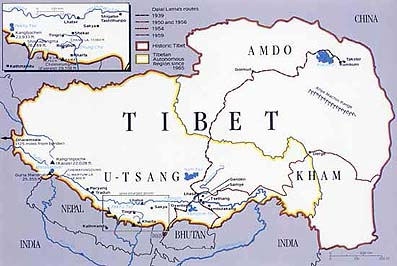

To Tibetans, Tibet includes all three traditional provinces of U-Tsang, Amdo and Kham. When China refers to Tibet, it means Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) which includes part of historic Tibet.

Shortly after the Chinese occupation of Tibet in the 1950s, China carved up Tibet into various administrative regions. U-Tsang and part of Kham came under the Tibet Autonomous Region, and Amdo and the remaining part of Kham were incorporated into Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu and Yunnan. Tibetan regions in the Chinese provinces are labelled as Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures. Many Tibetan towns incorporated into the Chinese provinces are today widely known by their Chinese names. For instance, Yushu Tibet Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai province is to the Tibetans Jyekundo in Kham province.

3) What is the population of Tibet?

Historic Tibet has an estimated population of about 6 million Tibetans and 7.5 million Chinese settlers, meaning that Tibetans have become the minority in their own country. Roughly 3 million live in the Tibet Autonomous Region, what China refers to as Tibet.

The Chinese Government has incentivised settlement of Han Chinese in an effort to extinguish Tibetan culture and identity. “The population transfer from China to Tibet is following the same policy implemented in China-occupied Mongolia (today’s Inner Mongolia) during the Qing Dynasty, where Mongolians were already a minority in the end of the 19th century.”

4) An overview of modern Tibetan history

Tibet was an independent nation, existing next to China for centuries, with its own national flag, currency, stamps, passport and army. In 1912, the 13th Dalai Lama issued a proclamation reaffirming Tibet’s independence. As a country, it signed treaties and maintained diplomatic relations.

In 1950, a year after the Chinese Communist Party came to power, China sent in troops to seize control of Tibet. In 1951, Tibetan government representatives signed the controversial 17 Point Agreement, which codified that Tibet would be allowed self-governance if its leadership agreed Tibet would become part of the People’s Republic of China. This document is viewed as invalid by Tibetans as it was signed under duress. Pockets of resistance simmered over the next few years. In 1959, there was a Tibetan uprising spurred by fears of a plot to kidnap the Dalai Lama and take him to Beijing. On 10 March, which is now commemorated as Tibetan Uprising Day, 30,000 Tibetans surrounded the Norbulingka Palace. The uprising was brutally crushed by the Chinese army and led to the Dalai Lama’s escape into exile in India.

Subsequently Tibetans suffered very badly during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s when many monasteries were destroyed and many people were made destitute. The era of Deng Xiaoping led to a brief relaxing of the tight controls in Tibet but after the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989 and the change in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership restrictions were again imposed. Major uprisings occurred again from 1987-1989 and then in 2008 preceding the Beijing Olympic Games.

To look at a timeline of Tibet’s history over the last century, see here.

5) Why did China invade Tibet?

For China, possessing Tibet gave access to rich natural resources, a strategic border and increased its landmass by roughly 25 per cent, an area the size of Western Europe.

From copper to iron ore to lithium, Tibet holds immense stores of essential minerals craved by the modern Chinese and global economies. Until a few decades ago, Tibet was protected by its remoteness, its vast mineral reserves mainly beyond reach. This changed as the Chinese government poured billions of yuan into new infrastructure, opening up Tibet’s once inaccessible riches to industrial exploitation.

Sandwiched between the two Asian powers of China and India, Tibet is both a buffer against China’s neighbours and a road to them. Invading Tibet in 1950 gave China considerable geostrategic leverage in South Asia. China has many military forces throughout Tibet and particularly along the border areas. There have been recent clashes between Indian and Chinese troops along the border.

The size and under-development of Tibet meant opportunities for Chinese settlers to migrate and start businesses (frequently to the detriment of the local Tibetans).

6) Why is Tibet called the Third Pole?

Tibet, the world’s largest and highest plateau, is known as Earth’s Third Pole because it has the largest reserves of freshwater outside the Arctic and Antarctic. Control over Tibet means control over this immense water resource. Tibet is the source of most of Asia’s great rivers – the Ganges and Brahmaputra in India, the Indus in Pakistan, the Irrawaddy in Burma, the Salween and the Mekong, upon which much of Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand, depend and the Yangtze and the Yellow in China.

The Tibetan plateau is warming at least twice as fast as the global average and the impact of the now melting glaciers are catastrophic because its water is a lifeline for millions of people downstream. Tibet is therefore at the forefront of the impact of climate change so Chinese government environmental policies are critical by preventing further logging of catchment areas and minimising soil degradation. Unfortunately, rather than consulting with Tibetan nomads who had nurtured the plateau over many centuries, Chinese authorities have been forcibly moving nomads off their land into unsuitable housing on the outskirts of towns where they have no work and suffer a loss of culture and identity. Read our report ‘An Iron Fist in a Green Glove’.

7) Human rights in Tibet

Political oppression and surveillance

According to the Freedom House 2021 ranking, Tibet is the least free place in the world, tied with Syria.

While human rights are limited across China, the situation is far worse in Tibet. Arrests, disappearance and torture are common means of suppressing dissent. Prisons in Tibet are filled with Tibetans detained for acts deemed by the Chinese government as threats to its authority. This could be participating in a protest or leading a community initiative for environmental protection.

Tibetans face intense surveillance in their daily lives. Tibetan towns and cities are dotted with security cameras, police checkpoints, security personnel and CCP informants closely monitoring their daily lives of Tibetans. Tibet has been the laboratory of China’s repressive policies. Chen Quanguo, the chief architect behind the incarceration program in East Turkistan (Xinjiang), was the CCP boss in Tibet Autonomous Region from 2011 to 2016. It was there he experimented with extreme surveillance measures – the “grid management” system. In the absence of strong international opposition, Quanguo was posted to East Turkestan where he took the repressive measures to an alarming new level. Meanwhile, the intrusive systems of security have continued to persist in Tibet. Tibetans live in a climate of fear, and the Party-State seeks to control every aspect of public and private life.

China controls the spread of information in Tibet through strict monitoring and censorship over social media, emails and telephone conversations. It also restricts the flow of information out of Tibet. Foreign journalists, tourists and diplomats are rarely allowed entry into Tibet and even they are, they are part of government-sponsored or controlled tours. Tibetans send information to organisatons and friends and families overseas at great risk of arrest and imprisonment.

Lack of freedom of religion

Tibetan Buddhism has flourished in various parts of the world. But sadly it is under severe attack in Chinese-occupied Tibet. Tibetans do not have the freedom to practice their religion meaningfully. They are arrested for merely keeping a photo of the Dalai Lama. Tibetans are told to put portraits of CCP leaders in their homes and also in monasteries, temples and public halls and in certain areas, officials go house to house to check that they are on the altar.

Monks and nuns are routinely forced to undergo ‘patriotic education’ which involves declaring their loyalty to the Chinese government instead of the Dalai Lama. The number of monks and nuns are also dictated by the Chinese government. In 2016 Chinese authorities demolished most of Larung Gar, Tibet’s largest centre for Buddhist studies, banishing about half the population, allowing only 5000 monks and nuns to remain. Similarly, in 2019, around 3500 monks and nuns were forcibly evicted from the Yachen Gar Tibetan Buddhist Institute.

The atheist Chinese government tries to control the ancient Tibetan Buddhist system of reincarnation. In 1995, the Chinese government kidnapped Tibet’s 11th Panchen Lama (Tibet’s second-highest religious figure after the Dalai Lama) when he was just six years old. China saw the young Panchen Lama as a future threat to its authority given the popularity of the previous Panchen Lama, a vocal critic of Chinese policies, among Tibetans. Six months after the abduction of Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, the Chinese government appointed its own Panchen Lama in a mockery of the ancient Tibetan Buddhist tradition of reincarnation. Tibetans refer to the Chinese Government’s appointee as Panchen Zuma (meaning the fake Panchen). Having kept the Panchen Lama in captivity for the last 25 years, China now plans to interfere in the reincarnation of the next Dalai Lama.

Attack on Tibetan language and culture

Tibetans have maintained a unique culture and language before China’s invasion in 1950. China’s policies ever since have been designed to wipe out Tibet’s unique cultural identity. The Tibetan language is the bedrock of Tibetan culture. But it is threatened by China’s policy of promoting Mandarin as the primary language in education, government and business.

There has been a concerted effort by the Chinese authorities to lessen the use of Tibetan, with the Chinese language being the medium of instruction in middle and high schools in Tibet and more recently this has been extended to kindergartens and primary schools. This has led to many young Tibetans losing their knowledge of Tibetan language and culture and this policy is part of an overarching program of cultural genocide.

In late 2015, language activist Tashi Wangchuk went to Beijing to appeal to the Chinese authorities to protect the language rights of his people. When his plea went unheard, he spoke to the New York Times about his campaign. He was arrested soon after his story appeared in the media and sentenced to five years imprisonment.

Socio-economic marginalisation and environmental destruction

Tibet is governed directly by the Chinese Communist Party. The nominal head (Chairman) of the Tibet Autonomous Region is Tibetan, but the Party Secretary, the most senior government post with the real power, has always been Han Chinese.

China’s exploitation of Tibet’s rich natural resources and the massive infrastructure development, including the construction of dams on Tibetan rivers, roads, railways and airports, are a threat to both the people and environment of Tibet. Chinese industrialisation has displaced millions of Tibetan nomads from their ancestral land, opening the land for extraction of resources and ending a traditional way of life that has sustained the Tibetan environment for centuries.

Chinese propaganda emphasises the developments that the government brought to Tibet. However, the economic progress in Tibet is primarily intended to consolidate China’s grip over Tibet and enhance its ability to exploit Tibet’s natural resources. The real beneficiaries are mostly Chinese migrants and businesses, who have a competitive advantage in urban areas where Mandarin is widely used. The vast majority of Tibetans are left socially and economically marginalised in their own country.

8) The Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Government in Exile

Soon after fleeing into exile in India in 1959, Tibet’s spiritual and temporal leader His Holiness Dalai Lama established the Tibetan Government in Exile, formally known as the Central Tibetan Administration, in Dharamsala. It was from there he led and built a successful Tibetan diaspora community across India and the world including Australia. In 2011, the Dalai Lama devolved his political authority to an elected leadership in exile.

Since the 1980s, the Dalai Lama has proposed the Middle Way approach to find a resolution with China over the Tibet issue. The policy seeks to attain genuine autonomy for Tibetans while remaining under the Chinese government. It is described as “a non-partisan and moderate position that safeguards the vital interests of all concerned parties-for Tibetans: the protection and preservation of their culture, religion and national identity; for the Chinese: the security and territorial integrity of the motherland; and for neighbours and other third parties: peaceful borders and international relations.”

However, China has failed to consider the proposal extended by the Tibetans in a spirit of compromise and reconciliation. Meanwhile, both within Tibet’s borders and in exile, Tibetans continue to resist China’s occupation of their homeland. They long to see their legitimate national aspirations fulfilled. They want to determine their future, and many continue to champion for Tibet’s complete independence from China.

9) Tibetans in exile and in Australia

There are estimated to be about 150,000 Tibetans in exile, mainly settled in India and Nepal but with large communities in North America, Europe and more recent arrivals settling in Australia. Many went into exile in 1959 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, with more following in 1980s after relaxation of regulations, and a subsequent slow flow escaping across the Himalayas either to escape political or religious persecution, or for children to receive a Tibetan education in the refugee settlements mainly in India.

Tibetans started arriving in small numbers in the 1970s and 80s but their numbers have increased since 1997 through the Australian government’s humanitarian program for Tibetan refugees, most of whom are former political prisoners and their families.

There are now about 2500 Tibetans living in Australia as of 2020, with local community associations established in major cities across the country.

Our Tibet Story

Lobsang Norbu, the survivor

Watch and listen to the story of Lobsang Norbu, who survived 24 years as a political prisoner in Tibet under Chinese-occupation.

Tenzing Yeshi, the musician

“I was born in exile, and it is music, first and foremost, that connects me to my Tibetan roots.” Listen to Tenzing Yeshi’s story.

Lobsang Jinpa, the monk activist

Read Lobsang Jinpa’s story. He was awarded the Reebok Human Rights Award 1988. ” In my monastery room, I wrote about the human rights situation in Tibet.”

Tenzin Deky, the youth leader

Watch and listen to the story of Tenzin Deky. “My parents were former political prisoners and they sought refuge in Dharamsala in northern India, after escaping Tibet.”

Lobsang Lungtok, the community leader

Here is Lobsang Lungtok’s story. “I’m not the first Tibetan to have been imprisoned for something I wrote…now live in Australia, where I can speak freely and without fear of persecution.”

Tibet reading lists

Tibet documentaries and movies

The documentaries and movies in this list we’ve put together explore Tibetan stories of hope, courage and belonging and give insight into issues surrounding China’s occupation of Tibet.

Spring Reading List: Member recommendations

With the arrival of Spring we bring you a new reading list, with recommendations from our members ranging from classic to contemporary. Enjoy!

Winter Reading List: What our community is reading

Enjoy this Tibet winter reading list featuring recommendations given by our members and supporters, ranging from historical accounts to personal narratives.

Our Summer Reading List: 12 books by Tibetan writers

Starting this month, we will be bringing you our pick of the best books, movies, food and all things Tibet. Our first Summer Reading List is dedicated to Tibetan writers from Tibet and in exile. From politics to Buddhism, here is our pick of 12 all-time favourite books.