Tenzing Yeshi, the musician

There is a Tibetan saying that “Anyone with a mouth can sing, and with legs can dance.” Tibetans sing anytime or anywhere; whether they are working in the fields, grazing their animals on the grasslands or celebrating special occasions. Our music is woven by our history, land and spiritual beliefs.

I was born in exile, and it is music, first and foremost, that connects me to my Tibetan roots.

My parents were among the early wave of refugees who followed His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, into exile in 1959. Tibetan refugees went to start their new lives in various parts of India, but mainly in the south. Some, including my parents, settled in Darjeeling, a beautiful hill station in the east. Music made our simple lives in exile richer and happier.

I was introduced to music from a young age and vividly remember my father enjoying chang (Tibetan beer) with his friends, singing and making merry in the evenings. My mother also loved to sing and dance, so it was natural that when I went to the local Central School for Tibetans I joined the music group. We would perform on special Tibetan occasions like the Dalai Lama’s Birthday and Losar (Tibetan New Year), as well as at big Indian hotels in town. We also travelled to other places in India to participate in cultural competitions.

My father died when I was in Year 7. As the only son in our family, I felt a strong responsibility to support my mother and three sisters, so in addition to playing music, I did well in my studies and became a school prefect.

Good students were expected to go to university to study medicine or engineering, and I studied science in Years 11 and 12. That meant leaving Darjeeling to attend a school in Mungdod, in southern India. Compared to Darjeeling, Mungdod had a strong Tibetan community and it was there that I learned more about Tibet and our political struggle.

When I finished school I went to university to do a bachelor’s degree in science, which led to a job as a science teacher at the Tibetan school back in Darjeeling. Unfortunately the school had to close for a few years due to lack of funds.

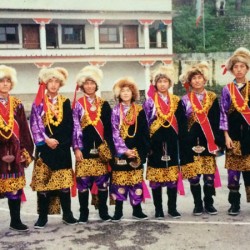

In my school dance group

As a dance teacher in Darjeeling

While I was figuring out what to do next, I came to know about a course in teaching music in Dharamsala, the seat of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. I had realised that music was part of my destiny and that I should embrace it whole-heartedly. While working as a science teacher I had often heard the dance teacher playing the dranyen – the Tibetan lute – in the neighbouring classroom. In my heart I wished to be in his place. My two-year training gave me a deep understanding of Tibetan music, art and culture. I found that being able to express myself through music boosted my esteem.

It was at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts in Dharamsala that I met my future wife, an Australian named Bridget. I was learning English from her and she was learning Tibetan and music from me. It was our shared passion for music, however, that brought us together. When Bridget had to return home, I went back to Darjeeling to work as a music teacher. I loved teaching music to kids and started a band with the students, ensuring all students in the school had the opportunity to play and enjoy music. It gave me great joy to pass on Tibet’s rich music and culture to the new generation of Tibetans.

In 2009 I moved to Australia to spend my life with Bridget. Now I work as a childcare teacher in Melbourne, a job that I love. Tibetan music is still a big part of my life; in my free time, I teach music to young Tibetans in Melbourne and perform at festivals. I’ve found that music is a wonderful way to share Tibetan culture, our struggle and our history with the world.

With my wife Bridget

Performing at the Festival of Tibet in Brisbane

Through my music I can raise funds for projects I believe in. My friend Tenzin Lobsang and I have a small group – the Australia New Zealand Tibetan Youth – that raises funds for orphans in Tibet.

While I am able to freely play my music in Australia, many Tibetan artists in Tibet are denied this simple joy. Musicians in Tibet are like the unofficial spokespersons of our society. They use their music to celebrate our culture, remember our rich history and express their sadness over the political situation in Tibet. They also use their music to express their devotion to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and other spiritual teachers. The musicians’ popularity is perceived as a threat by the Chinese government, which is why so many of them are arrested and imprisoned.

I long for the day when musicians in Tibet and in exile can unite and perform together. I long for the day when we can sing in freedom about Tibet’s natural beauty and culture.

Performing at a rally in Melbourne

Peforming with young Tibetans in Melbourne