Tenzin Deky, the youth leader

I, Tenzin Deky, was born in exile like so many other Tibetans before me, and many more after me. My parents were former political prisoners and they sought refuge in Dharamsala in northern India, after escaping Tibet. I was only two years old when we moved to Australia – one of the first Tibetan families to migrate here under a special program for former Tibetan political prisoners and their families – and I’m now nineteen.

We made our home in the northern Sydney suburb of Dee Why; the area is a magnet for Sydney Tibetans. Here, by the beach, it is difficult to imagine anywhere more different to my parents’ village, in the high mountains of Tibet. Tibetans have learned to adapt well to new environments; it could be our nomadic background, but more likely it is the experience of being forcibly displaced from our homeland and having no choice but to make good in a new country.

Although my parents spoke little English when they arrived, they were determined to make a good living so that they could give me the best opportunities. They never went to school themselves, so wanted me to have the best education Australia could offer. They worked long hours in a supermarket to earn the fees to send me to a private Christian primary school. It was not long, however, before they felt conflicted; the strict Christian traditions were foreign to them. As Tibetan Buddhists we respect and value all the world’s religions, but naturally my parents were keen for me to be raised in my own tradition. They decided I should move to a public school, where I would be more able to be myself.

Early school years brought different challenges; while my Australian friends had their parents on hand to help with their homework, mine were still learning to read and write English. Although they could not help with my schoolwork, my parents were a powerful link to Tibet and kept me grounded in its heritage and values.

As the small Tibetan community in Sydney grew, a weekend school was established to teach Tibetan language and music to young kids like me. It was there I learned to write in Tibetan and began singing Tibetan songs. My friends and I were pleased to give cultural performances at our festivals such as Losar, the Tibetan New Year, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s birthday.

More than anything else, it is through Tibetan music that I have been able to form my own Tibetan identity. When I was a child we had a single CD of Tibetan songs that we played on the daily trip to the school and the weekly trip to the shopping centre. As more Tibetan songs appeared on YouTube, I became passionate about playing Tibetan music myself. The songs transported me from my bedroom in suburban Sydney to the lush, green meadows of the Tibetan plateau.

I have been singing at our local community functions from a young age.

Performing at a fundraiser for Regional Tibetan Youth Congress, Sydney

At my local Tibetan community function

The Tibetan community in Sydney is made up of a large number of former political prisoners and their families. My own parents spent three years in Chinese prison for simply sharing photos and teachings of His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. Others have spent up to twenty years in jail as a result of participating in protests or expressing views considered ‘unfavourable’ to the Chinese government. Many of us still have family in Tibet with whom we hope to one day be reunited.

As a young girl, I attended Tibetan rallies in Sydney with my parents, at which we called for freedom in Tibet. I waved Tibetan flags and lent my own voice to the others chanting “Free Tibet, China Out of Tibet” and “Human Rights in Tibet”. To be honest, I don’t think I fully understood those slogans; it was when I turned twelve, in 2007, that everything began to make more sense. Early in the year I attended a rally in Sydney demanding the release of Tibetan political prisoner, Tenzin Delek Rinpoche. He was a community leader who had dedicated his life to protecting Tibetan culture and its environment, but because of his standing in the Tibetan community, the Chinese government viewed him as a threat. Tenzin Delek Rinpoche was arrested and given a life sentence for a crime he had clearly not committed. I had been asked to read the story of this Tibetan lama. It was while recounting the story of this brave Tibetan, in public, that I suddenly began to truly understand these slogans.

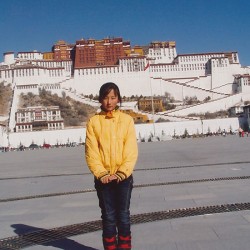

That same year, I first set foot on the Tibetan soil. Although I had heard so much about the situation in Tibet, seeing it with my own eyes was an altogether different experience. I spent a month in the capital, Lhasa, and another month in my dad’s village in Kham province. Although I was only young, that trip to Tibet made a great impact on me. For one thing, I had expected Tibetans to outnumber Chinese people – this was Tibet after all – but the Chinese presence was overwhelming. The streets of Lhasa were full of Chinese businessmen, police and tourists; from the Potala Palace to the rooftops of the Tibetan houses in my father’s village, the red flag of the Chinese was everywhere.

At 12, I read the story of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche at a rally and understood the meaning of freedom.

In front of the Potala Palace, Lhasa, 2007

In the cities, there were Tibetans who appeared happy and relatively rich, enjoying the trappings of urban life and spending their evenings in karaoke bars and expensive restaurants. Below the surface, however, was a different story. In these people I sensed a deep and unspoken dissatisfaction. They were reluctant to talk about politics and focussed, instead, on the material pursuits in their life. In the cities, the wide gap between the rich Chinese and the poor Tibetans was striking. Where my cousin attends school, lessons are in Mandarin and Tibetan has become a secondary language.

When I returned to Australia my interest in Tibetan identity and culture had grown. My lessons in Tibetan music and language became more serious and meaningful. It was natural, then that I became involved myself in political activities. In 2008 – as Tibetans across Tibet took to the streets to protest against China’s rule in the lead up to the Beijing Olympics – I took part in a three-day peace march to Canberra to express solidarity with the Tibetans in Tibet.

At university I’m undertaking a Bachelor of Science, majoring in Statistics, but am also learning Mandarin. I can now talk to Chinese people about Tibet in their own language.

Last year, I was elected as the vice-president of Sydney Regional Tibetan Youth Congress. We organise social, cultural and political events to engage young Tibetans in the Tibet cause. At the beginning of 2014 I went to Canberra with other young Tibetans from across Australia to lobby politicians. Some politicians were supportive of the Tibetan struggle for freedom and justice, others less so. How can Australian politicians help us, they wondered, when China is so powerful? Politics change, however, and power shifts. What doesn’t change is truth, justice and people’s desire for freedom. I believe that when politics change, truth, justice and freedom will prevail. If we younger Tibetans live and celebrate our rich culture, and remain hopeful and committed, Tibet must flourish.

Speaking at a rally in Sydney

With Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young on Tibet Advocacy Day in Canberra

At Sydney Opera House