Lobsang Norbu, the survivor

From a monk to a warrior

I was born the son of a farmer in Phenpo in central Tibet in 1934. At six years old, I became a resident monk at Sera Monastery in Tibet’s capital Lhasa. In 1959, at the age of 25, I joined the Lhasa Uprising against the occupying Chinese forces. Even though I was a monk, I had no choice but to take up arms to defend my country from foreign invasion.

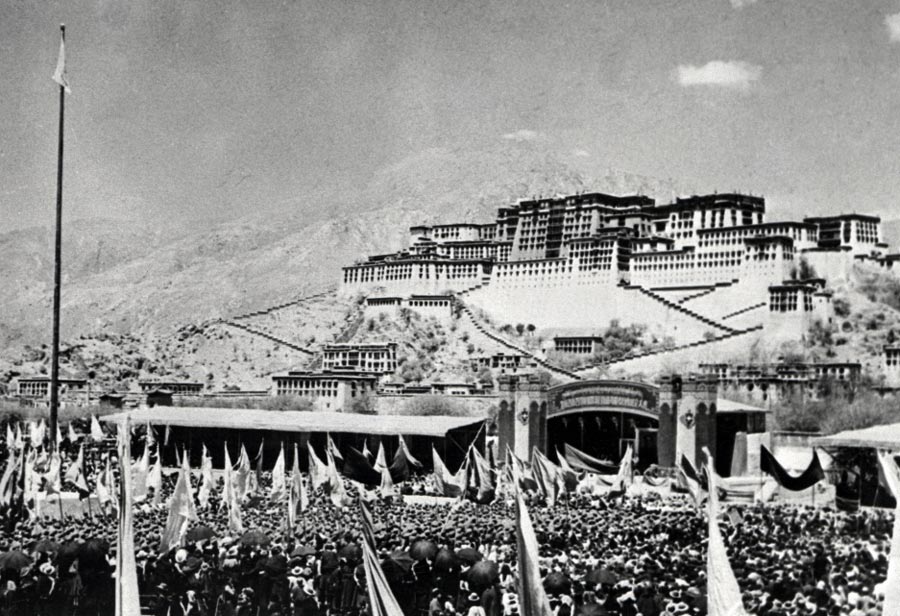

Tibetan National Uprising in 1959, Lhasa

On 10 March that year, a huge crowd of Tibetans, including many of my relatives, surrounded Norbulingka, the summer palace of the Dalai Lama, to protect our leader. Rumours had spread across Lhasa that the Chinese government would kidnap the Dalai Lama that day. We held an urgent meeting at our monastery that night. The abbot of our monastery asked for ten volunteers from each of the 16 hostels to join an armed resistance against the Chinese troops. He told us it was time to put aside our self-interest and fight for our nation. I immediately volunteered.

On 19 March, at around two am, the Norbulingka was heavily bombarded by the Chinese troops. I still remember the incessant shower of bullets and the piles of dead bodies strewn everywhere. It was unimaginable. Chagpori, Lhasa’s medical college, was also destroyed. The Tibetans were too ill-equipped and untrained to resist the Chinese troops, who came with their advanced artillery. We had rifles; they had machine guns. But we did not give up and put up a good fight.

The monks and I soon fled to Phenpo from where we continued to fight. There were just nine of us left, so we were badly outnumbered. Some surrendered and returned to the monastery. I went to Lhokha and joined Chushi Gangdruk, an organisation of Tibetan guerilla fighters, who had helped facilitate the Dalai Lama’s escape to India a few days earlier. It was there I came to know that His Holiness had fled into exile.

On 26 March, we went to defend Chak Sam Chuwo Ri, the temple of Thangtong Gyalpo. We fought the Chinese troops head on for two days. On the third day, our base was bombarded in the middle of the night, killing many of my mates. I was severely wounded in my abdomen and could not flee the scene on my own. I was captured and imprisoned.

Thus began my long journey of torture and imprisonment by the Chinese government. In prison, I did not receive adequate medical treatment for my injuries. It was only after escaping to India, more than two decades on, that I was able to seek proper medical care with the support from the Tibetan Government-in-Exile.

24 years in prison

After my arrest on that fateful day in March 1959, I was locked up in solitary confinement at my monastery for six months. I was tortured and told to confess guilt over my actions and disclose the names of my accomplices. When I refused, I was sent to a prison to be “reformed”.

Many of the inmates at the prison died of starvation. We were not fed for days and ate scented grasses that even cows would reject. I also ate human bones. One day I noticed a fellow monk quietly chewing on something. I asked him what he was eating when others were dying of hunger. He had found bones of dead prisoners. He shared some with me on the condition that I didn’t tell anyone. In any case, I would not brag about eating human bones. Soon the prison guards came to know what we had been doing. They cleaned up all the remaining bones in prison and buried them.

The food given to us was simply not enough as we were forced to work for 12 hours daily at construction sites. From the early days of Chinese rule, the government started building dams on Tibetan rivers using prisoners as labourers.

In 1959, the prisons were filled with Tibetans who had not done anything to harm the Chinese government. Many of these innocent Tibetans were later released while the prominent leaders of the uprising received prison sentences ranging from ten to twenty years.

Those who were arrested from the battlefield, like me, were released in small groups on the condition that we denounce His Holiness the Dalai Lama and put our fingerprint on a document that stated: “Tibet is a part of China”. I did not like the idea. I knew the Chinese would use these forced confessions by the Tibetans to legitimise their rule in Tibet. I refused to accept their proposal. For that, I was given a seven-year prison term and stripped of political rights for a lifetime.

I was later moved to Drapchi, Tibet’s largest and most notorious prison. Prisoners were dying daily from torture and undernourishment at this prison. When fifteen people lost their lives in one day, the prison authorities launched an inquiry. They summoned me for the interrogation. They claimed that there was an outbreak of a disease, but I knew that was not the case. I openly criticised the Chinese government’s policy and accused them of ethnic cleansing. The Chinese government was not only killing our people. It was also erasing our history and destroying our religion and culture. In prison, we were forced to urinate on Kangyur Tengyur, our sacred Buddhist texts. I had made up my mind to speak out. Having seen many Tibetans shot to death or die from starvation, I was counting my days and was not afraid.

Towards the end of my seven-year prison term, the prison officials showed us a Japanese movie depicting the “cruelty of Japanese imperialist rule” and how Chinese children were separated from their parents for many years. During the discussion on the film, I stood up to voice my opinion. I accused the Chinese of doing the same thing to the Tibetans. I pointed out that I had not been allowed to meet my parents over those seven years.

One day the Chinese officials brought my mother to see me. They told me I would be released if she expresses her regret over my actions and her gratitude to the Chinese Communist Party for the prosperity it has brought to Tibet. She was told to address a gathering on behalf of Tibetan commoners.

My mother refused to give in. She told the officials she could not do it because she had seen only the sufferings of the Tibetan people after the Chinese came to Tibet. She then told me to continue to fight until we received justice. She even warned that she would disown me if I was released by expressing my guilt and denouncing His Holiness the Dalai Lama. She said she would be proud of me even if I died in the cold prison fighting for my country.

So the Chinese officials extended my sentence and I ended up spending 24 years in prison.

I have no regret

I spent many months in solitary confinement at Drapchi. The prison authorities would interrogate and torture me every day – from morning till night. They would not let me sleep until midnight. They broke my legs and arms. I had to get a knee implant after my knees were broken into pieces. All this happened because I refused to name my accomplices and denounce my guru.

The officials even forced fifteen of us Tibetan political prisoners sign a document with our execution dates. By then, I was mentally prepared to die, but they spared some of us. I vividly remember how we were made to watch the execution of our fellow inmates.

To me, the Communist Chinese government is the most notorious terrorist in the world. It is a shame that the United Nations is incapable of taking action against China. The UN has the responsibility to support the oppressed people. However, today money is more powerful than truth and justice. No nation can openly call out China for its heinous crimes against humanity because of economic self-interest.

In 1977, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping declared that the prisoners from 1959 to 1960 would be released. Again on the condition that we accept China’s sovereignty over Tibet. I refused to accept this proposal even after facing many years of torture and imprisonment. So I continued to remain in prison for a few more years.

In 1982, I appealed to the Chinese authorities to release me on the grounds of my “good behaviour” in prison. I told them I was one of the longest serving Tibetan prisoners.

On 1 December that year, I was released from prison. It seemed like a miracle. I never imagined during those 24 years that I would one day walk out of prison, go to India, meet the Dalai Lama and eventually move to Australia.

I am 83 now, and as I look back, I have no regrets over joining the Tibetan resistance movement as a 25-year-old man back in 1959. But the fact that I lost most of my family members as a result of my actions continues to haunt me to this day.

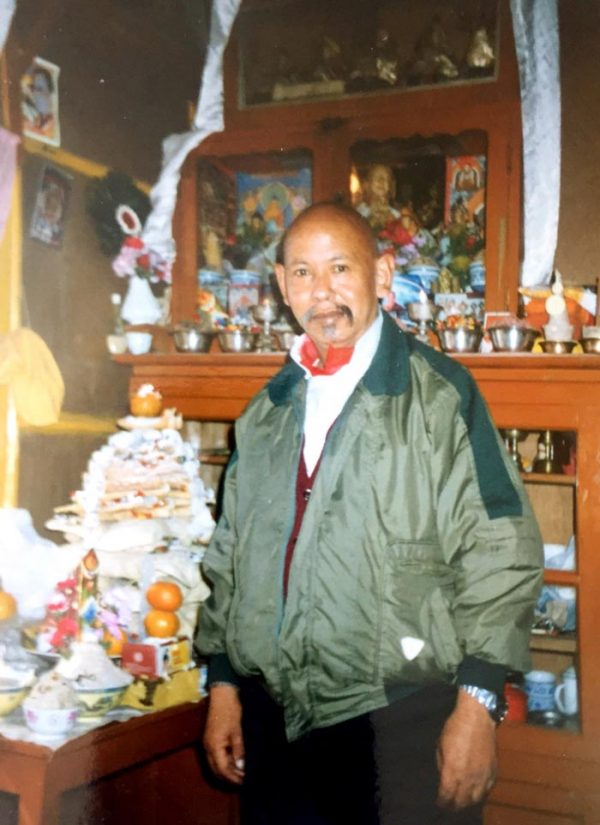

At home in Tibet

An audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama

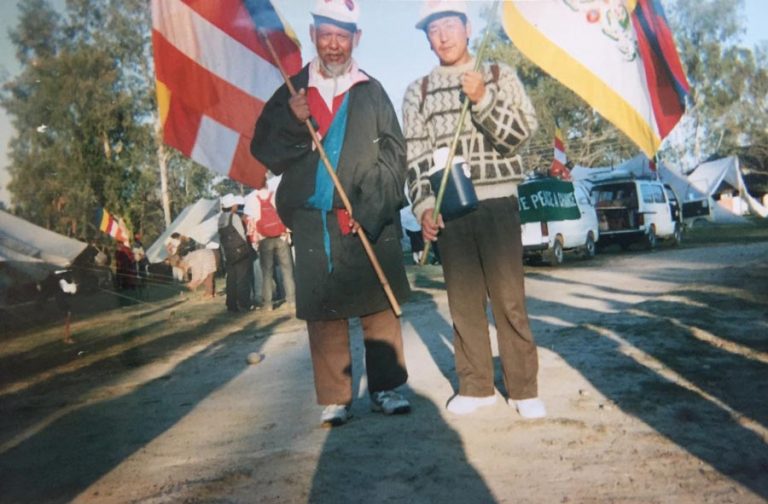

Peace march from India to Tibet, 1995

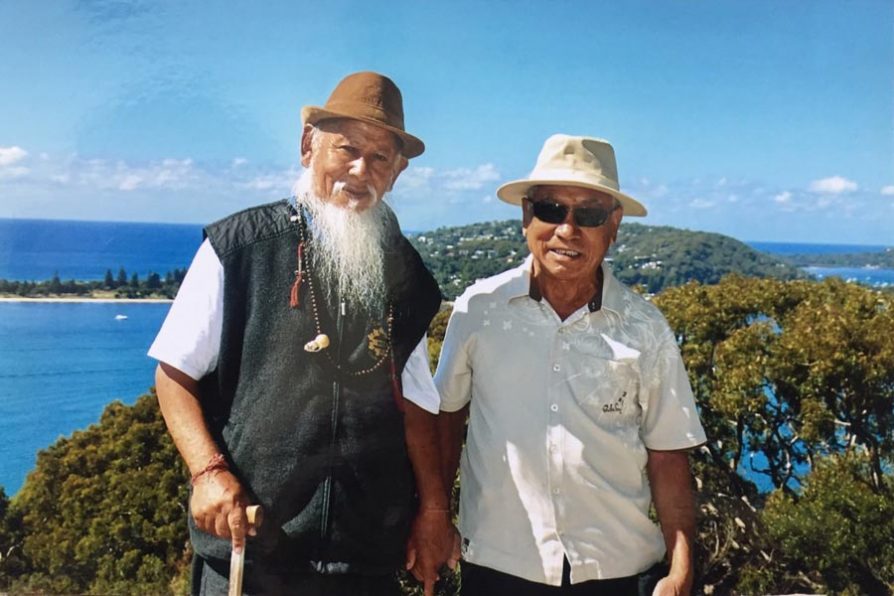

With a Tibetan friend in Sydney