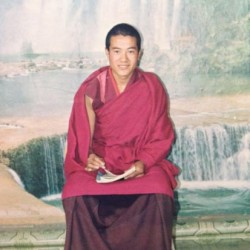

Lobsang Lungtok, the community leader

I, Lobsang Lungtok, am not the first Tibetan to have been imprisoned for something I wrote. Although I now live in Australia, where I can speak freely and without fear of persecution, but my peers and relatives at home resort to self-immolation to express Tibet’s plight.

Chang Kya – the small Tibetan village in the north-eastern province of Amdo, where I was born – takes its name from the brown willows that line the Gu Chu River. Before the Chinese army breached Tibet’s eastern border in 1950, my mother lived the simple life of a farmer. This farming lifestyle was thousands of years old when China invaded with the promise of great development. Instead of development, my mother, my people, saw irreparable damage to their land, culture and livelihood.

The period in which I was born – the mid-seventies – was marked by the destruction of thousands of monasteries and the systematic attack on Tibetan Buddhism. It was the height of the Cultural Revolution and Mao’s Red Guards were on the rampage. Although I am a Tibetan, at school I was taught that my nation was China, my flag the red, five-starred Chinese flag and that I should be loyal to the Chinese Communist Party. Those lessons only reinforced my Tibetan identity; they triggered my political awakening.

At fifteen, I became a monk and joined the local monastery, Rongpo. Four years later, in March 1995, I was listening to an overseas Tibetan radio service and heard that the Tibetans in India were organising a peace march from Dharamsala to Lhasa. I wrote a poem in support of the march that said ‘Stand up, Come together, You should march for your rights’ and pasted posters on public buildings. It was not long before the police picked me up in the market and took me to prison. They asked no questions, there was no trial.

As a young monk at Rongpo Monastery

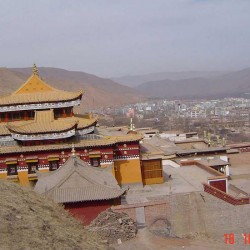

The town of Rebkong where my monastery is located

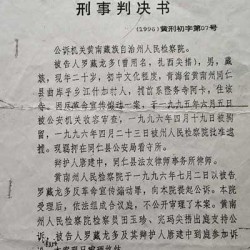

The Chinese document on my prison sentence

The conditions in prison were so harsh they made me sick; I had heart problems, constant headaches, acute pain in my joints and my nose bled for five months. They released me so I could see a doctor and I was sent home, where I remained under constant surveillance by the Chinese police. As soon as I was better I was re-arrested. Eventually there was a trial, but held in secret, at which I was sentenced to eighteen months in prison and charged with “promoting and publicising counter-revolutionary ideas with the evil intention of sabotaging the unity and solidarity of the nationalities, and harbouring the empty hope of Tibetan independence by following the separatist clique of the Dalai”. I was not defeated; I was angry.

“Who asked you to write that poem?” the authorities demanded. This is the same question they ask, repeatedly, of Tibetans today – “Who made you do this?” They are so blind to our suffering that they search for a conspiracy. I acted of my own volition; I do not believe that what I wrote was illegal.

Back in prison, the guards tortured and beat me and the other inmates without reason. I cannot stop thinking and dreaming of those times. I went to prison young and active, but left feeling like an old man. One day I received a secret message that my case was being re-investigated; with a heavy heart, I said goodbye to my mother and fled.

I headed for Lhasa, a place I’d dreamed of as a young boy growing up in a faraway village. I imagined that the Tibetan capital was a heaven, home of the Dalai Lamas, the Jhokhang Temple and the great monasteries, Sera and Drepung. The dream changed before my eyes as I arrived in the dirtiest city on the roof of the world. It was a mix of Tibetan beggars, Chinese restaurants, glitzy shops, karaoke bars and brothels, all with garish signs, predominantly Chinese-owned. The Potala Palace was being transformed from the living heart of Tibet into a museum; it was like a person who had lost his soul.

From Lhasa I travelled on foot for weeks through the snow-covered Himalayas to Nepal. Eventually I sought refuge in Dharamsala, in northern India, just as His Holiness the Dalai Lama and thousands of other Tibetans had done before me.

In Dharamsala, I learned my first English words and got my first job as a researcher for the London-based Tibet Information Network, an organisation providing news and in-depth research on the situation in Tibet. I interviewed and recorded the stories of the newly arrived refugees; they were monks, nuns, nomads, farmers, businessmen and children from all parts of the country. Now I could have candid conversations with a broad section of the Tibetan population. I gained a much deeper understanding of our struggle.

In 2002, I moved to Australia with my young family under the Australian government’s Special Humanitarian Program. Over the last fifteen years, over a thousand former Tibetan political prisoners and their families have come to Australia under this program. Although we inhabit a free country, we live with the pain of not being able to talk openly to our family members in Tibet. The Chinese government taps the phone conversations of Tibetans who have family members in exile; the only way for us to stay in contact is by avoiding topics on politics and the Dalai Lama. Phone and internet connections are cut when a protest breaks out.

Collecting signatures for a Tibet petition at a concert in Brisbane

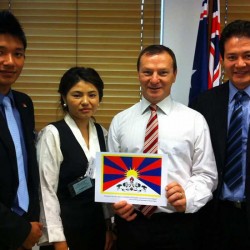

With young Tibetan-Australians on Tibet Lobby Day in Canberra

Lobbying for Tibet in the Australian Parliament

Adapting to a new life in a new country has never been easy, but loss can be transformative. Living in Australia has offered me new opportunities; I now speak freely about Tibet and live without fear of arrest and torture. With these privileges comes a strong sense of responsibility to help bring positive change for those inside Tibet.

The Northern Beaches suburb of Dee Why in Sydney became my first base in Australia. From a small apartment, I held meetings with my Tibetan and Australian friends and discussed ways to raise awareness about Tibet. With limited resources, we started the first magazine in our local Tibetan community. Published in both English and Tibetan, Tibetan Voice provided news and views about the situation in Tibet. Over the years, I became more active in my work for Tibet and recently became a director of the Australia Tibet Council. As a former political prisoner and a community leader, I have met politicians in Canberra and in my local electorate to build support for our freedom struggle.

Tibetans in Tibet live in a climate of fear. This is how China has been able to assert its control in Tibet over the past 60 years. After a visit to my mother in 2005, she revealed her intense fear that I would be re-arrested during my stay. When I visited Tibet in 2010 I witnessed attacks on Tibetan nomads, who have enjoyed their unique lifestyle for many generations. Nomads and their herds were forced in the hundreds of thousands from their ancestral land and “resettled”, in permanent housing that looked like army barracks, with devastating impact on their community and livelihood.

My village – Chang Kya – in Amdo

During a visit to my village in 2005

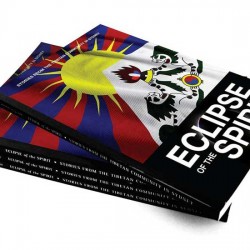

The book of Tibetan stories that I edited and produced with Australian friends

The area where I was born was known for its rich intellectual tradition and artisanship. In recent years, it has become a centre for resistance. Tibetans from all walks of life have risked arrest and torture in mass protests, demanding a better future for their countrymen. There, my young cousin, Tenzin Dolma, and my friend, Jamyang Palden, joined nearly one hundred and thirty others who decided they had no choice but to self-immolate. Jamyang, a monk, had little interest in politics, but he, like so many others, was denied basic rights and freedoms. Committing his body to fire was the most drastic form of protest.

When my Australian friends ask me how I feel about my homeland, I tell them it’s easy to feel hopeless when one looks at China’s rising economic and political power. I believe, however, that nothing – including China’s power – is permanent. With support from the international community, Tibet will change. It’s the Tibetans inside Tibet who give me the determination to never give up. The more the Chinese try to crush the Tibetans, the more they resist. In their homes and communities they keep our culture and identity alive. Our desire for freedom and justice keeps the flame of resistance burning.